In 1862, the Union Army was in striking distance of Richmond and the Union commander hoped to wrap up the entire war with just a few more engagements, but surprising aggression by the Army of Northern Virginia’s new commander would cause a Union defeat, leading to two more years of warfare.

Union Gen. George B. McClellan had been making his way towards Richmond as part of the Peninsula Campaign in 1862, but Gen. Robert E. Lee attacked and managed to turn the skittish McClellan south.

(James F. Gibson, Library of Congress)

In May 1862, the Union’s top officer was Gen. George B. McClellan, a railroad man turned military officer. While he had many drawbacks, his organizational skills were top notch and he had managed to fight way into position just miles east of Richmond, the political and industrial heart of the Confederacy. If he could capture the city, the Confederacy would fall apart or be forced to withdraw south to Atlanta or another city while losing massive amounts of manufacturing power.

And, the Confederacy had just fought a stalemate at the Battle of Seven Pines. Both sides claimed victory, but the Confederate commander was wounded and the Southern president promoted Gen. Robert E. Lee to the position. Lee was known for caution at this point in the war, and McClellan decided to take time to wait for good weather and reinforcements before pressing his attack home.

It was a hallmark of McClellan’s actions during the war, and it gave Lee time to order a large network of trenches dug, allowing him to defend the city with a small force while preparing the larger portion of his army for a much more aggressive move. Lee didn’t want to just defend Richmond, he wanted to attack the Union force’s supply lines, forcing a retreat.

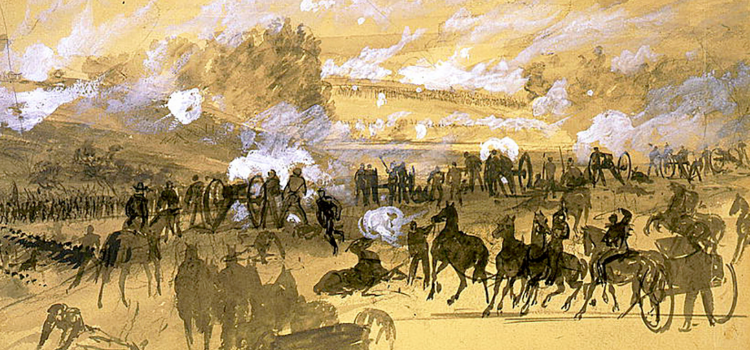

A sketch and watercolors depiction of the Battle of White Oak Swamp, one of the Sevens Days Battles.

(Alfred Waud, Library of Congress)

The Union Army in the field was much larger than the Confederates’, 100,000 facing 65,000. But the Union Army was fighting far from home and needed over 600 tons of supplies per day, almost all of it shipped by rail and packtrain from northern cities.

On June 26, with Stonewall Jackson drawing close with an additional 20,000 Confederates, Lee struck, starting what would become known as The Battle of Seven Days or the Seven Days Battles. The forces fought five major engagements and number of smaller skirmishes over that fateful week.

Lee began his assault when the Union Army was sitting astride the Chickahominy River with a third of it on the northern side and two-thirds on the southern side. That meant that Lee could attack the northern side and potentially even destroy the railroad there before the rest of the Union forces could get into position to fight him.

But day one, known as the Battle of Mechanicsville, went badly for the Confederacy. Lee committed his forces before Jackson had arrived, and Jackson was delayed by poor navigation and exhaustion from the long march and previous battles.

On day two, Jackson once again ran into trouble and Union forces were able to regroup, forming a united front against the Confederate forces. But McClellan still didn’t press home his numerical advantage, withdrawing under the assumption that the aggressive Lee outnumbered him.

On June 28 and 29, the Confederate forces were able to launch successful attacks against the retreating Union forces, but they were unable to land a crippling blow. And so, McClellan was able to reach a great defensive position on July 1. From Malvern Hill, he could defend against any number of Confederate attacks.

In the end, the Confederacy lost approximately 20,000 men while the Union lost 15,000.

McClellan’s failure to capture Richmond in 1862 caused the Civil War to drag on for two more years.

(Kurz & Allison, Library of Congress)

But while Lee had failed at his goal of landing a significant blow against Union forces, but he had succeeded in his larger goal. McClellan had been mere miles from Richmond and on the offensive, but one week later he was driven south, begging for more troops and supplies before he would attack again. Instead, he let Lee rebuild his forces and move north, achieving another victory at the Second Battle of Bull Run and opening the door for Lee’s first invasion of the North.

Lee, previously known for his caution, had gone on the offensive despite being outnumbered, and it had saved the capital and its industry. McClellan would later lose his command, partially because of the failure to attack Richmond and his failure to attack off of Malvern Hill.

Lincoln would have to go search for his own Lee, his own aggressive general to carry the attack against the enemy, to force the initiative. It took Lincoln another few years to get him into position, but this would eventually be Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, a man known at the time for his alcohol consumption and his butchery, but now possibly known best for receiving Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House, propelling Grant to a successful 1868 presidential run.

This article originally appeared on We Are The Mighty

More From We Are The Mighty

5 Reasons Why Troops Stick Together After the Military

4 Reasons Why Showering On Deployment is Disgusting

7 of the Greatest Songs Every Veteran Knows

6 Things You’d Take Back Before Leaving the Military

6 Dumb Things Veterans Lie About on the Internet

Follow We Are The Mighty on Twitter

READ NEXT: 5 OF THE BEST THINGS TO HAPPEN IN THE FIELD

READ NEXT: 5 REASONS WHY YOU’LL NEVER FORGET YOUR FIRST DRILL SERGEANT

READ NEXT: 5 OF THE MOST ACCURATE MILITARY REPRESENTATIONS ON SCREEN